Inscription

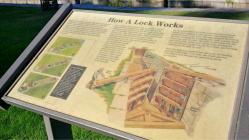

Instead of following the slope of the land, as rivers and streams do, a canal periodically takes a vertical step between long stretches of flat water. Locks were constructed at each vertical step to accomplish moving barges up and down between each of the long stretches of flat waterway. The vertical step at this lock is 12 feet. The lock's hand-operated mitre gates, while simple in concept, required close attention and experience to operate.

At the boatman approached a lock, he would sound an alarm a half to a quarter of a mile away, alerting the locktender. Entering the lock was the most demanding part of canalling. Canal boats were usually designed to fill as much of the lock as possible. Thus a boat would enter the lock with only inches to spare. If the helmsman allowed the boat to hit the lock walls, he could damage the lock walls or even sink the boat. Nevertheless, the boat had to be moving fast enough to go all the way in the lock, yet still had to be stopped before it hit the gate at the other end of the lock. Crashes of this sort were a major cause of damage to the canal, as boatmen would often race each other to get to the lock first.

As the boat entered the lock, a crewmember jumped ashore and wrapped a rope around a snubbing post anchored next to the lock. The rope stopped the boat in the lock. Working the snubbing post took a steady hand. If the rope was too tight, the boat would crash into the side of the lock, or the post would snap, sending the boat into the gate at the far end. Too loose and the boat crashed into the gate as well.

Once the boat was snubbed into the lock, the locking process could begin. Generally, the whole process of locking a boat through the gates took about ten minutes.

At the boatman approached a lock, he would sound an alarm a half to a quarter of a mile away, alerting the locktender. Entering the lock was the most demanding part of canalling. Canal boats were usually designed to fill as much of the lock as possible. Thus a boat would enter the lock with only inches to spare. If the helmsman allowed the boat to hit the lock walls, he could damage the lock walls or even sink the boat. Nevertheless, the boat had to be moving fast enough to go all the way in the lock, yet still had to be stopped before it hit the gate at the other end of the lock. Crashes of this sort were a major cause of damage to the canal, as boatmen would often race each other to get to the lock first.

As the boat entered the lock, a crewmember jumped ashore and wrapped a rope around a snubbing post anchored next to the lock. The rope stopped the boat in the lock. Working the snubbing post took a steady hand. If the rope was too tight, the boat would crash into the side of the lock, or the post would snap, sending the boat into the gate at the far end. Too loose and the boat crashed into the gate as well.

Once the boat was snubbed into the lock, the locking process could begin. Generally, the whole process of locking a boat through the gates took about ten minutes.

Details

| HM Number | HMAQ |

|---|---|

| Series | This marker is part of the Susquehanna and Tidewater Canal series |

| Tags | |

| Historical Period | 19th Century |

| Historical Place | River |

| Marker Type | Historic Structure |

| Marker Class | Historical Marker |

| Marker Style | Free Standing |

| Marker Condition | No reports yet |

| Date Added | Thursday, September 4th, 2014 at 11:38am PDT -07:00 |

Pictures

Photo Credits: [1] SEPTEMBERSPARROW1666 [2] SEPTEMBERSPARROW1666 [3] SEPTEMBERSPARROW1666 [4] SEPTEMBERSPARROW1666

Locationbig map

| UTM (WGS84 Datum) | 18S E 406075 N 4379055 |

|---|---|

| Decimal Degrees | 39.55605000, -76.09328333 |

| Degrees and Decimal Minutes | N 39° 33.363', W 76° 5.597' |

| Degrees, Minutes and Seconds | 39° 33' 21.7800" N, 76° 5' 35.8200" W |

| Driving Directions | Google Maps |

| Area Code(s) | 443, 410 |

| Can be seen from road? | No |

| Is marker in the median? | No |

| Closest Postal Address | At or near Park Dr, Havre de Grace MD 21078, US |

| Alternative Maps | Google Maps, MapQuest, Bing Maps, Yahoo Maps, MSR Maps, OpenCycleMap, MyTopo Maps, OpenStreetMap |

Is this marker missing? Are the coordinates wrong? Do you have additional information that you would like to share with us? If so, check in.

Nearby Markersshow on map

Show me all markers in: Havre de Grace, MD | Harford County | 21078 | Maryland | United States of America

Maintenance Issues

- Who or what organization placed the marker?

- Which side of the road is the marker located?

Comments 0 comments